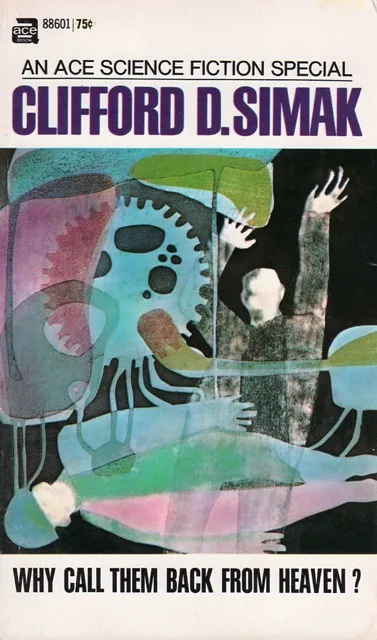

Why Call Them Back From Heaven?

Clifford D. Simak and the Idea of a Cryonics Society

A Cryonics Dystopia

In science fiction, cryonics, far from being a fringe pursuit, is virtually a given. Whether it’s Sigourney Weaver in Alien or Han Solo in The Empire Strikes Back, sci-fi characters are freeze-dried and thawed straight out of the fridge with complete, casual abandon.

Indeed, cryonics is so much of a given that its meaning and impact is generally overlooked. It’s just an assumed fact, like faster-than-light warp drives. The technology is merely an excuse for the story: the implications of such technologies is simply passed. Rarely are they meditated upon.

As far as cryonics goes, that is unique distinction of one single, classic novel—Clifford D. Simak’s 1967 novel Why Call Them Back From Heaven?

In this novel, Simak—author of such classics as Way Station, City, and Time Must Have A Stop—gives us a vision of a world utterly remade by the promise of resurrection technology. Here is a civilization that has staked everything on the assumption that death is merely an intermission, a technical problem awaiting a technical solution. In this small science-fiction masterpiece, cryonics is not science fiction, not an eccentricity: it’s an integral part of society, an everyday fact of life around which life calmly revolves.

In Simak’s twenty-second century, The Forever Center corporation operates with the bland efficiency of an insurance conglomerate, yet dominates with the totality of a state religion. Humanity has reorganized itself totally around a single axis: the preservation of the dead and the economic machinery necessary to revive them once technology permits. Here capitalism and immortality are locked in an eternal waltz, each leading the other toward a horizon that recedes with every step taken; for there, as here, restoration from cryonic sleep is not yet achieved. One thinks of those medieval cathedrals that took centuries to complete—except here the cathedral is made of liquid nitrogen and actuarial tables, and the resurrection that is the object of faith is the future self, perfected and imperishable.

Meaning and Merely Existing

What Simak understood, with the clarity that marks the finest speculative fiction, is that cryonics is not merely a medical procedure but a theology. It has to fit within a framework of meaning to be desirable at all. Mere technological capacity is a secondary issue. His protagonist, Daniel Frost, works within the Forever Center’s vast bureaucratic apparatus, a true believer until the moment his belief falters.

The novel’s central tension—Frost’s suspicion that the Center may be perpetrating a fraud—is less a thriller’s McGuffin than an existential crucible. If resurrection is a lie, what then? Has the cryonicist mortgaged the present for a future that will never arrive? Has such a commitment to the future only fostered the ultimate civilizational suicide? Simak’s

Yet to read Why Call Them Back From Heaven? as a cautionary tale against cryonics would be to miss the forest for a single, admittedly prominent, tree. Simak’s genius lies in his ambivalence, that most literary of virtues. His world is one in which the promise of preservation has indeed created a kind of living death—people defer gratification, postpone meaning, treat their current existence as a mere rehearsal for the glorious second act to come.

The birth rate has plummeted: why bring children into a world you’re planning to escape? Culture has ossified: why innovate or create when you have all eternity to do so—later. The planet groans under ecological strain while humanity’s gaze is fixed on the stars, on Mars and beyond, where the resurrected billions will supposedly find new worlds to inhabit.

But is this deferral a failure of cryonics, or only a manifestation of the human capacity to mortgage today for tomorrow? Simak never quite answers, and that refusal is the novel’s abiding strength. Consider: we already live in a civilization predicated on deferred gratification, on the promise that sacrifice now will yield rewards later—retirement accounts, insurance policies, the whole edifice of modern financial planning. We already treat our bodies as vehicles to be maintained, our lives as projects to be optimized. Cryonics simply extends this logic to its ultimate conclusion, asking us to invest not merely in our old age but in our rebirth, our second chance at the cosmic lottery.

The pro-cryonics reader—and I confess my own sympathies here—will find in Simak’s novel not a refutation but a challenge. If we are to pursue preservation beyond death, we must do so with full awareness of what we may lose in striving for even more life.

The question is not whether resurrection is possible—that remains, as it does in Simak’s novel, a matter for future generations to determine—but whether a life and a civilization built around that possibility can remain human, can retain its capacity for joy, spontaneity, the quotidian pleasures that make mortality bearable, meaningful, and occasionally beautiful.

Simak’s prose marches forward with workmanlike efficiency, and the reader need rarely pause to admire the stride. Yet Simak’s empathy is such that few of his books feel more literary. In his cryonic dystopia, it’s a crime — and your option for immortality is revoked — to not attend to a body that has recently died. One such character has his chance at immortality revoked after being found guilty of not aiding a recently deceased, yet still tries to provide for his families immortal existence. The scenes are moving, as are the vignettes featuring the ‘Holies,’ those still holding to conventional faith.

But Simak doesn’t load the dice. Those committed to cryonics, and those resistant, get equal measure of sympathy; and there is something appropriate, even moving, in this restraint. He’s writing about a world that’s sacrificed aesthetic richness for utilitarian purpose, beauty for function, and his style mirrors that sacrifice without entirely succumbing to it.

The novel’s title, drawn from a rhetorical question posed by one of its characters, contains within it the entire ethical dilemma. Why call them back? Because death kept them from being all they could have been. Because they were denied their full span of years. Because technology failed them when it might have saved them. Because we failed them: because we owe a debt to those who came before us, those who brought us into being and shaped us.

An Expanded Finitude

It’s said that we should we let the dead rest, accept mortality as the price of meaning, understand that it is our finitude that makes our choices matter.But do death and finitude really give meaning? Why? Would Beethoven’s life, or Plato’s, or Shakespeare’s, have been more meaningful if they’d been aborted in the womb? Would society have been ‘enriched’ by such an amputation?

Simak doesn’t say. He doesn’t have to. Why Call Them Back From Heaven? endures not because it settles the debate about life extension but because it frames that debate with unusual sophistication, social scope, and surprising tenderness.

But the debate is wrongly framed. The choice is not between endless immortality and obliteration. What we want is an expanded finitude—a life in which all our potentialities are realized. A life we leave only when it’s been entirely fulfilled. Threescore and ten—or less—is not that life.

For those of us who look at cryonics not as hubris but as hope—the realization that consciousness is too precious to waste, that the accumulated wisdom and love of a human life should flourish, not be discarded and forgotten—this novel stands as both warning and inspiration.

Why Call Them Back From Heaven? reminds us that the technology of resurrection, should it ever arrive, will be the easy part. The hard part will be shaping a future that is worth entering, and a life that is worth preserving.

Copyright 2025 by The Cryonics Society

Note: all text and commentary in the Cryonics Society web site may not be reproduced without the written prior consent of the authors.

Direct mail inquiries to:

Cryonics Society,

P.O. Box 90889,

Rochester, NY 14609,

USA.

Email: contact @ cryonicssociety.org

Tel.: 585-473-3321